The flashbacks are always the same. Ajmal Ahmadi is transported to August 4, 2010, when a roadside bomb exploded under his Humvee in north-east Afghanistan. There was an explosion, a fireball, blackness – then screams.

When the smoke cleared and gunfire stopped, Ahmadi’s commander, Lieutenant Tim O’Donnell, was dead.

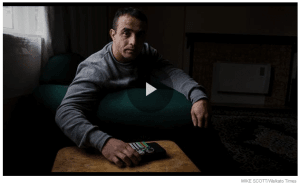

Ahmadi is now safe in Hamilton – but his nightmares have followed him. Diagnosed with post traumatic stress disorder, he has trouble sleeping and can’t hold down a job. He’s had casual work, but now collects a sickness benefit. He has few friends, lives alone in a military-neat one-bedroom flat in Hamilton east and has little to do with other Afghan interpreters. “Of course I am lonely,” he says.

Ahmadi, 26, is haunted by the terrible things he saw while working as an interpreter for the New Zealand Defence Force but even worse, he fears he’ll never see his family again.

Because he came here under a special cabinet deal and not as a refugee, he is unable to apply for his parents and five siblings to join him. Only those with spouses and children could bring their loved ones with them – singles had to come alone.

Most of the 44 interpreters who’ve resettled here brought wives and children – 96 additional family members in total have migrated to New Zealand.

Ahmadi says he wasn’t told his family would be ineligible, and wants the Government to reconsider. His family is in danger from the Taliban because of the work he did, he says.

“I put my life on the front line and now it’s time for the New Zealand government to give a hand and help me with my family.”

Ahmadi has a lot of supporters – a Hamilton lawyer has worked tirelessly for him pro bono, the RSA’s district support advisor has taken up his case in Wellington and military officials have agitated on his behalf.

His local MP, National backbencher David Bennett, went in to bat for him but was unable to sway his colleague, Immigration Minister Michael Woodhouse.

“While I appreciate Mr Ahmadi’s circumstances in New Zealand and his concern for his parents and siblings in Afghanistan,” Woodhouse wrote to Bennett, “I am not prepared to intervene.”

His lawyer, Jane Walker, says if Ahmadi had arrived as a refugee, he would have been able to apply to bring his family under the family support category.

“He needs his family to support him. Not only can they not come, but he can’t go back, so he’s in no-man’s land.”

She has asked Woodhouse to make a ministerial direction under the Immigration Act, as he did to grant residency to Ahmadi in the first place.

Immigration NZ says once the interpreters have been residents for three years they might be eligible to sponsor their parents for residence.

Walker says for that to happen, the applicant has to be earning at least $60,000 a year – highly unlikely in Ahmadi’s case, because of his PTSD.

“It’s very difficult for Ajmal,” she says. “He sees other refugees in New Zealand who haven’t [served with the army] and they’re allowed to bring family in and he’s not. I think it’s morally indefensible what’s happening to him.”

At a special ceremony in Napier in March, army chief Major General Dave Gawn presented Ahmadi and another former interpreter with service medals, telling them they had made an invaluable contribution to the army and New Zealand.

Everyone agrees he’s served his new country bravely and loyally: he just can’t have his family here.

“HE WAS MY BEST FRIEND”

Ahmadi was just 16 when, in 2004, he walked into the New Zealand’s Provincial Reconstruction Team (PRT) base near his home in Bamiyan province and applied for a job as a translator.

He was from a wealthy family. His father had a large farm growing wheat and potatoes and also worked as a construction supervisor for a French NGO.

His mother worked for the UN’s World Food Programme. They owned three houses.

The family are Hazara Shia, an ethnic group persecuted for centuries. In their home village they were surrounded by Tajak Sunni and Pashtak people, many with extreme religious views, and were forced to move around the province to escape the Taliban.

Ahmadi, known as AJ to his army buddies, ended up working for the PRT for seven years, becoming one of their longest-serving interpreters.

Did he like the work? “It was interesting, I had a good time. I also had a bad time.”

The good: Being able to support his family and make new friends.

The bad: Retrieving bodies, being ambushed by Teleban insurgents, watching friends die.

The worst: The death of his commanding officer, O’Donnell.

“He was my best friend. He was really friendly, a good person. We used to talk… he was not like my commander.”

On the afternoon of August 4, 2010, four Humvees were returning to the Kiwi forward patrol base Romero after a mission to deliver supplies to villages.

At 4.30pm, the vehicles reached a dry river bed just south of the village of Karimak. O’Donnell sat in the front passenger seat of the lead Humvee. Ahmadi was seated behind him.

The convoy was navigating a hairpin bend when suddenly there was a huge explosion from a roadside bomb. The Humvee caught fire.

Ahmadi lost consciousness. When he came to, he clambered out of the vehicle and made his way to the river bed. His hands, face and hair were burnt and he had eye injuries.

The unit continued to take fire until about 6pm, when Afghan police arrived and secured the area.

The wounded, including Ahmadi, were taken to the Bagram military hospital. Ahmadi was discharged after a few days. He returned to work, but had nightmares and constant anxiety.

He was given some medication and left to fend for himself.

GERMANY

Towards the end of 2011 Ahmadi decided to leave the country to seek treatment, making his way to Turkey and then Germany, where he was sent to a refugee camp near Dortmund.

After about six months, he was told he might be able to go to New Zealand.

The Government had agreed to take 23 interpreters who were working for the PRT. But former interpreters were excluded from the offer, described by critics as “lean” compared to other countries.

A couple of months later the deal was extended to include former translators such as Ahmadi, but they had to have worked for the PRT within the past two years.

Ahmadi was interviewed by an Immigration NZ officer in Germany. He says he told the officer he was worried about his family and needed to look after them. “She said she would send copies of my family’s passports to New Zealand, which I provided.”

Immigration NZ says Ahmadi was told about family residence categories and the requirement for him to be in New Zealand for three years before he could sponsor extended family.

Ahmadi was granted residency in November, 2013 and arrived in Auckland early in 2014. Again, he says, he was told he would be able to apply for family to come later.

“I’d worked hard and I’d been through a lot. I believed I would be able to bring my family.”

A FAMILY’S PLEAS

“Jon Key, please safe our life,” says the hand-written sign held up to the camera by Ahmadi’s brothers and sisters.

“I worry about them,” he says. “Every time I call them they say they are not feeling safe. A couple of months ago one of our relatives was kidnapped by insurgent people.”

Ahmadi’s siblings are 12 to 24, single and speak English.

If they were allowed to come to New Zealand, Ahmadi says, his parents would sell their property, worth about $1m.

Walker says Ahmadi’s situation is unique.

He worked for the army for much longer than the other interpreters, she says. Almost all of the others had wives and children who were able to come with them.

In a letter to Woodhouse, Walker described Ahmadi as being in a “serious humanitarian situation”.

Woodhouse was asked why he wasn’t prepared to make an exception.

He dodged the question, a spokesperson saying the Government “recognises the valuable contribution made by interpreters” but the deal was for spouses and children only.

None of the other 44 interpreters had been able to bring wider family members, the spokesperson said.

Mark O’Donnell, who met Ahmadi when he went to Afghanistan after his son’s death, says he can’t see why his family can’t come. “If his family want to come here and they’re not a drain on society, what’s the issue?”

Ray Terrill, the RSA’s Waikato support advisor, says he finds it “very strange” that Ahmadi isn’t allowed to be reunited with his family. “The whole thing seems unjust to me.”

Terrill travelled to Wellington this week to take up Ahmadi’s case with Veterans’ Affairs, and to see about a disability pension. “I’m rattling cages all over, I think he’s been poorly treated.”

Labour’s former Defence Minister, Phil Goff, has also written to Woodhouse. He says the minister could treat it as a one-off case given Ahmadi’s “extreme” experience in Afghanistan and his “total absence of family support in New Zealand”.

Rachel O’Connor, Red Cross refugee services manager for Waikato, says most of the 30 or so interpreters and their families who settled in the area have integrated well, finding jobs or studying.

But for some, it had been a struggle. “For anyone new to New Zealand, being separated from their family is incredibly difficult.”

Ahmadi has no regrets about working for the army; he’s glad he did it. But it’s clear from the worry and sadness in his eyes that he’s not in a good place. He puts it simply: “I’ve suffered a lot.”

Source: Stuff news